What’s happening?

You care about the environment. So you pay extra attention when you go to your local shops to buy the things you need, so you choose a product with a sustainability label rather than one without. BUT, in some cases those labels don’t matter because they may still be linked to deforestation and human rights abuses.

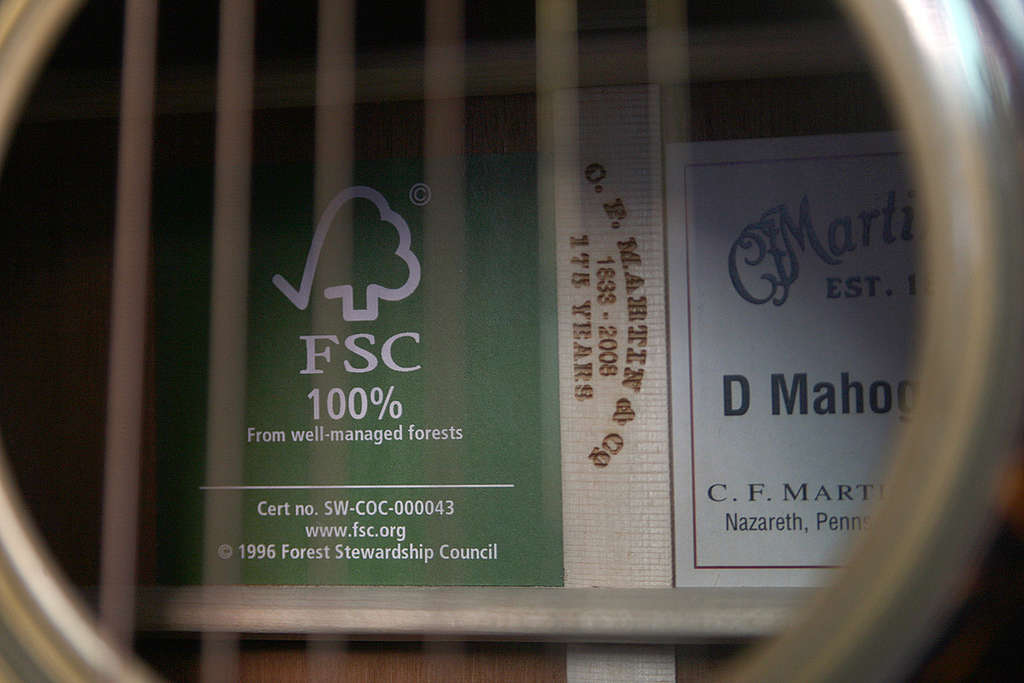

In Greenpeace International’s new report, Destruction: Certified, we looked at certification labels on cocoa, coffee, biofuels, palm oil, soy and wood. Labels that you may recognise, like FSC, PEFC, Rainforest Alliance Certified, NSF Sustainability Certified, Green Tick and more. We compared these ‘certifications’ against the reality of how companies using these labels actually address the problems of deforestation, forest degradation, ecosystem conversion and human rights abuses, including violations of Indigenous rights and labour rights.

The results are in: many of these certification schemes enable destructive businesses to continue as usual.

Why does it matter?

While certification has become increasingly popular globally over the past decades, deforestation and ecosystem destruction has continued.

From the Amazon to the Congo Basin to Indonesia, in Europe and North-America, companies are destroying forests to exploit the land and its resources. 80% of global deforestation is a result of agricultural production. Meat, dairy, soy for animal feed, palm oil, pulp and paper, and cacao drive demand for more and more agricultural land. Whether directly or indirectly, many households consume all these products. You want to know that the ‘certified’ thing you’re buying is really sustainably sourced.

By certifying their products as ‘sustainable’, companies drive up demand and increase the harm caused by their extractive production. And so, while we think we’re making the right choice, we might actually be buying products linked to abuse and destruction.

Through the use of misleading labels, companies are relieving themselves of their responsibilities and pushing it onto us. Protecting forests and human rights shouldn’t be optional, and the burden shouldn’t be on consumers, to skim through all the labels and make sure we’re not falling for greenwashing.

How did we get here?

In the early 1990s, following a wave of environmental awareness in the consumer world, many companies and governments made commitments to fight deforestation. They looked to certification as the answer.

What is ‘certification’ and forest certification?

Certification is a verification process through which an owner of a farm, a fishery or a forest can indicate they comply with social or environmental standards, and earn the right to sell their products as certified. Certified products often include consumer-facing ecolabels. Companies producing or trading “forest and ecosystem-risk commodities” often rely on certification to reassure customers. They want to show that they or their suppliers have taken action to minimise the negative environmental and social impacts linked to production, so their products can be considered ‘sustainable’.

So should we stop buying certified products?

No. Some certification schemes have a positive impact locally. Sometimes labels, like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), can help guide consumption choices. The same goes for organic food (which is outside the scope of this report and is an example of a regulated label and so much more trustworthy). But, whatever the certification scheme, checking each label, its promises, and whether or not it actually delivers requires a lot of research. That’s difficult to do when you’re looking to buy something off the shelf.

Instead, we need to force our governments to change their policies to protect people and the planet.

What you can do.

Together, we can push governments and businesses to seriously address the problem of deforestation and human rights abuses.

Governments in producer countries need to be courageous in regulating companies and rolling out stronger legislation to protect natural habitats. Governments in consumer countries need to set up transparent tracking systems and adopt laws preventing the sale of products linked to destruction and rights abuses. All governments need to stop relying on corporations to fix these issues voluntarily.

Companies need to step up their game with strong environmental and social standards to make sure their supply chains are not contributing to forest destruction.

Stronger laws and bigger efforts to reduce the consumption of certain products are essential if we want to tackle the climate, biodiversity and inequality crises, and create a healthier society.

Grant Rosoman is a forest campaigner with Greenpeace International

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.