Maverick Flores

Under the scorching afternoon sun, 21 year-old Joemar Pauig digs for fully-grown taro and purple yam from the shallow earth. Accompanied by his mother and younger brother, he loads the root crops on his horse for their descent from their hilltop farm in Daraitan, Rizal, east of Manila.

“I go up here to harvest every three days since I also have other jobs, like cleaning the other people’s gardens,” Joemar said.

Since childhood, Joemar and his fellow Dumagat Remontado, the indigenous peoples (IP) native to the area, were taught the ways of farming as a means of livelihood and survival.

“Even now, farming is still what we teach and pass on to the next generation because our land cannot be left underutilised,” said Maria Clara Dullas, president of the women’s group Kababaihang Dumagat ng Sierra Madre (KGAT). “We plant food so that we can make use of our land and sustain ourselves with nature’s bounty.”

Today’s community’s harvest is a special one. It would not only put food on their own tables, but also for hundreds of people lining up daily in Metro Manila’s community pantries.

Since April, community pantries have sprouted all over the Philippine capital and throughout the country. More than just a repository of edible goods, the community pantry has become a social phenomenon— a force for good where ordinary people give and donate food to those who are hungry, or hardest hit by the lockdowns and layoffs due to the pandemic. With community pantries, everyone is welcome to partake and contribute. The only rule is for people to take only what they need, and to share only what they can afford to give.

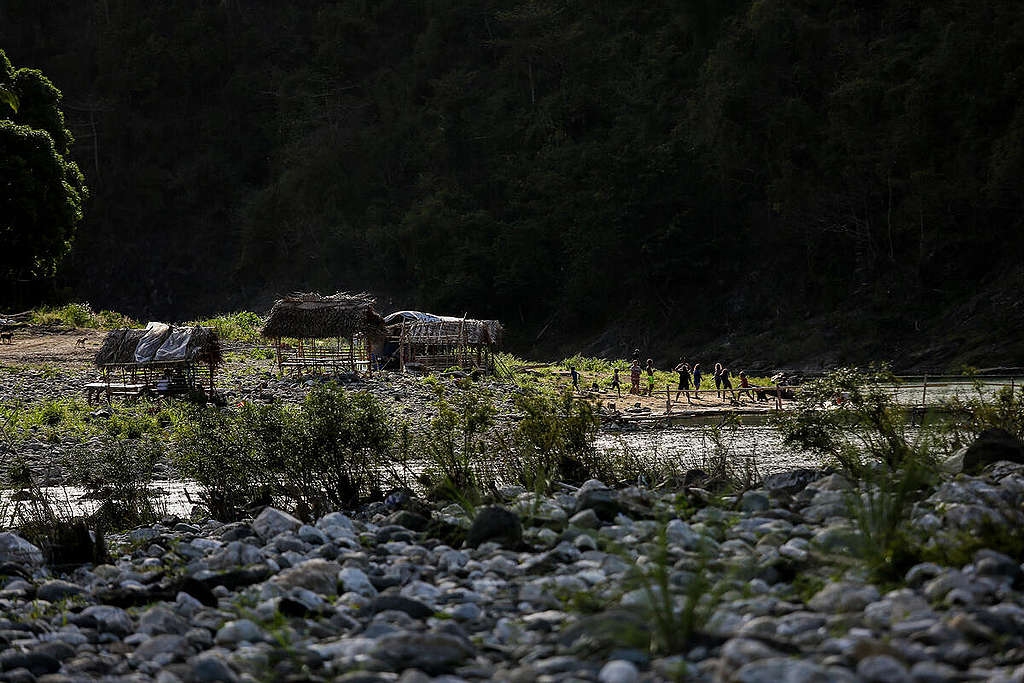

Despite the distance and a deadly virus, the Dumagat Remontado responded to a non-governmental organisation’s call for vegetables supplies for community pantries.

Those who fled

The Dumagat Remontado are no stranger to hardships and have endured countless trials as indigenous peoples. The word Remontado is of Spanish origin and means ‘to flee or go back to the hills’. The Dumagat Remontado are descendants of lowlanders who fled to the mountains to escape from Spanish colonisers centuries back.

Present-day Dumagats have been in the news, fighting for their rights and opposing the construction of the Kaliwa Dam on their ancestral lands that would flood Daraitan and neighboring areas in Quezon Province. If approved, the project would force their tribe and other non-IP residents to move elsewhere.

“Some of our sacred places will also be submerged. We haven’t seen the actual plans and a lot of us don’t agree with this project, but they’re always reporting that we already consented to it,” Maria Clara said.

The Dumagat Remontado actually experienced severe flooding last year when Daraitan was hit by Typhoon Vamco, a powerful and deadly typhoon that inundated Metro Manila and other provinces for days. The community’s indigenous beliefs guided them but in the end, they found themselves needing aid. Thankfully, many civil society organisations responded.

“We had visions of when the flood would come and how big the water was going to be,” said Renato Ibañez, leader of Dumagat Remontado group SUKATAN-LN. “We were told that if at noon and the water rose- as if the wind was carrying it- that means a disaster is coming. So our elders advised us to evacuate.”

Returning the favor

For most of the Dumagat Remontado farmers, they had only recently heard of community pantries- a movement that started when an unassuming young citizen decided to put one up along Maginhawa Street – an area known for restaurants and food parks. It has inspired thousands to step up, get organised, and do more for their own communities.

Despite their ongoing legal battles and economic hardships due to the pandemic, Maria Clara said these problems will not deter the Dumagat Remontado from helping others. Their community was able to contribute to at least 10 community pantries.

“We also want to show the government— or anyone who represents them in the Kaliwa Dam project— look at the food we’re getting from the areas where the dam is being built. The areas you will be flooding. These can feed a lot of families,’” she remarked. “‘Do you want to destroy this? Or should we support the IPs further and stop this project?’”

For their part, community pantries, such as the Sustainable Community Pantry in Pinagbuhatan, Pasig, are grateful for the vegetables the Dumagat Remontado farmers provided. “We thank the Dumagat Remontado because they are the real symbols of bayanihan (the Filipino term for working together to help those in need) – whatever they have, even if it was just enough, they still shared it with us,” said pantry organiser Lou Mercado.

Prior to receiving goods from the Dumagat Remontado farmers, Lou and his fellow volunteers had an ingenious way of stocking their community pantry, where dozens of people line up for help. They “rescue” food that are still edible, but considered unsellable, from the nearby wet markets.

Let it not go to waste

Maria Clara and her fellow Dumagats are happy to see their countrymen enjoy the fruits of their labor. But she hopes those who benefited from this endeavor will not let the food go to waste. “Don’t waste any kind of food, even one tiny piece. Because if you add all those together, they could still feed a lot of people,” she said. “Be thankful for the people who paved the way for community pantries because that means there are people out there who want to volunteer for their communities.”

As for Dumagat leader Renato, he sees these efforts as steps to build and solidify solidarity between the Dumagat Remontado and the city folk, and to boost the nation’s spirit especially during these tough times. “I told our fellow IP farmers that what we’re doing is helping people– it’s not just us asking for others’ help. From my perspective, with this food, all of us in this country are eating as one— we’re not divided, we’re not fighting, and we’re all dining from one table.”

Maverick Flores is a Communications Campaigner with Greenpeace Southeast Asia- Philippines. He advocates for indigenous peoples’ rights and social justice. In his spare time, he does podcasts and plays basketball.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.